Worthy Objects: Hassan Rahim Talks Shop with Use All Five

Hassan Rahim is an artist and art director working in New York. He is a recent winner of an ADC Young Guns Award. We spoke to him about art directing for Marilyn Manson, making objects, and the importance of BMW.

Much of your art has a physical manifestation–albums, clothing, books. Is that deliberate? Why are objects important to you?

Hassan Rahim: Because they exist—they’re present, here in time and space. You acquire them; they serve a purpose. What else is there?

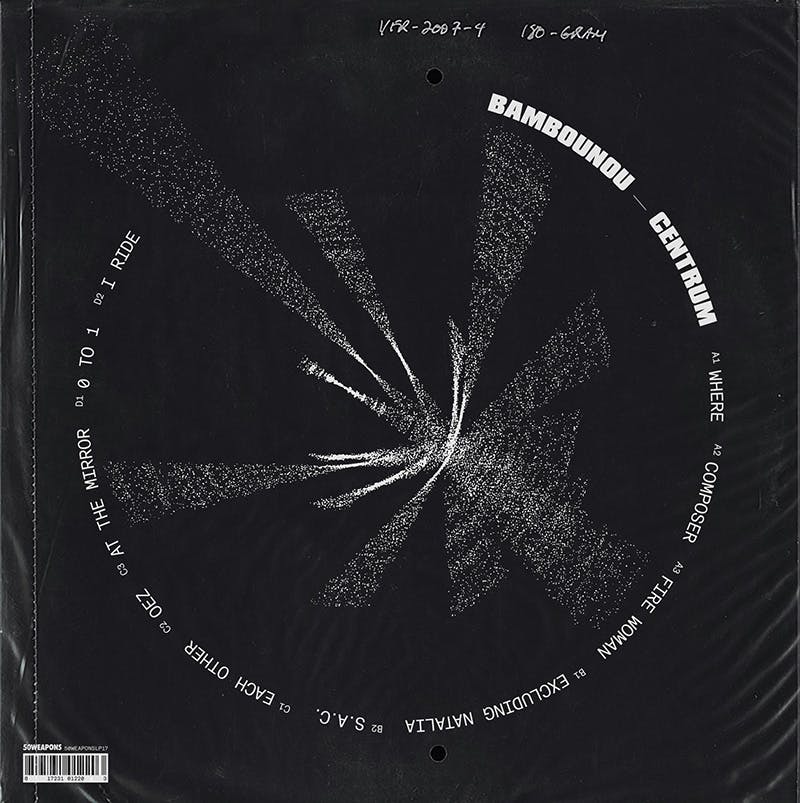

I need physical things. I wouldn’t call myself a hoarder, but I collect, sometimes to a detriment but always with intent. I always have and will obsess over ephemera, whether rare and specific or just a dollar bin gem. What I seek often has a specific cultural history; a lenticular boarding pass from the maiden voyage of Tokyo’s first Shinkansen, a Peter Gabriel record wearing my favorite Hipgnosis art, a first edition copy of Kohei Yoshiyuki’s book The Park. These things possess a deeper significance to greater culture than to me as an individual.

On the other hand, every object also carries a very personal history. Dents, scuffs, scratches, stains, folds, tears; each one has a story. Who owned it, where did they buy it, what did it mean to them? What chapters in their life did it bookmark? These unique histories are why I often find the process of acquisition more satisfying than the object itself. Engaging with the owner, hearing their story, leaving with a smile—all in turn making the object that much more meaningful.

In my own work—whether records, shirts, books, or other—I can only hope to create objects worthy of holding on to, cherished enough to one day hold their own unique place as footnotes in someone’s life.

These unique histories are why I often find the process of acquisition more satisfying than the object itself.

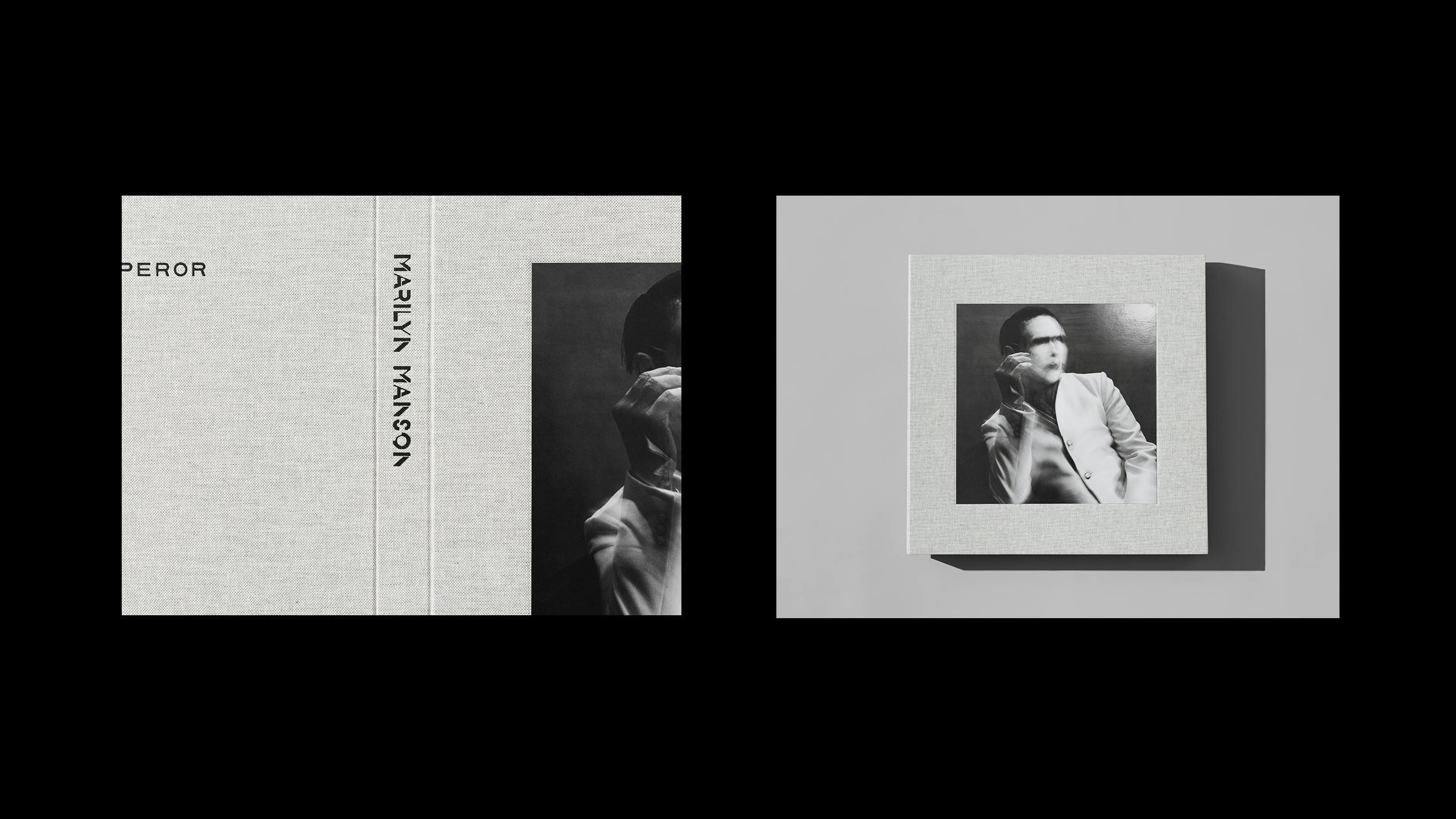

Last year you did the art direction for Marilyn Manson’s album The Pale Emperor. In a project like that, how much freedom do you have in the concept and the details? Since you’re trying to represent the music, how well does the final product reflect your own artistic identity?

Hassan Rahim: When an artist is receptive to even your most insane ideas, it really leaves all doors open. It was challenging but a very gratifying experience. Sometimes I had to sit back and remember all he has done for music and pop culture, how long he’s been around, the impact he’s left. Then, how could we do something new, a maturation from previous aesthetics but with the same attitude? At some point it actually wasn’t about representing the music, but instead the legacy he’s built. What a stressfully high honor to hold.

Willo Perron and I were up late on Skype almost every night throughout the project, throwing the wildest ideas we could come up with directly at Manson. Luckily the stars all aligned, and the end result became one of the clearest reflections of my artistic identity to date, as much as a commercial project could live up to be. I realized the responsibility of communicating his legacy was actually advantageous. It allowed malleability in the thought process, providing a wider lens to look through beyond the one album and essentially becoming more like a rebrand. Once those doors began to open, we just ran through them.

Let’s imagine there are magically more hours in the day. Are there any mediums you’d like to get into that you haven’t yet explored and why?

Hassan Rahim: Photography is another medium that I somewhat explore already, but at my own leisure, and only on projects when it feels right. But I feel exploring photography is equally about having enough hours in the day as it is about affording very pricey equipment. Depending what you want to do, it can easily cost 5 figures for a proper studio setup. Of course you can rent equipment, but all the fun is in experimentation, and who wants to put a return date on that? For now I make do with my iPhone for daily snaps, a Kyocera T-Zoom when traveling, and the occasional DSLR on projects.

At a much later stage, I’d love to experiment with music production. I’d always obsessed over synthesizers as a kid; I would skate to Guitar Center in Buena Park and spend hours on the microKORG and MS-20. They had to ask me to leave because real customers would be trying to demo them. When I was 15, I was on Limewire one night and decided to get every program I could get. By the morning I had Photoshop, Illustrator, and Fruity Loops, amongst dozens of others. I never got into Fruity Loops even after a bit of messing around; once I’d experienced an analog synthesizer maybe I just couldn’t get into making music on a computer. Eventually I shifted focus from Fruity Loops to Photoshop and got sucked in immediately (here we are).

Once in that context, I believe the idea of the BMW as a status symbol is entirely thrown out the window. No longer does it represent actual luxury, but the perceived concept of luxury from an exact time and place.

Why is BMW as a brand important to you?

Hassan Rahim: My own obsession with BMW stems from my childhood. My dad and uncle both had bimmers, E30 and E21 respectively. Even at 5 years old I understood the special feeling of riding in them versus any other car. The leather seats, the sound of the engine starting, the oily smell of the leaky engine gasket. Before his injury, on Saturday mornings I sat shotgun and my dad and I drove from Garden Grove to Hawthorne. We’d get McDonald’s fries and park the car just adjacent to LAX, watching the planes take off until sunset. That car symbolizes a feeling of bliss cemented in me forever, one I’d would give the world to have again for just a moment.

As a larger symbol, that same BMW represents many things from the perspective of an underprivileged black boy, growing up with nothing but knowing you deserved everything. One would be blind not to see a parallel with BMWs and their representation throughout black culture—from Ill Will’s 850i on the Nas Street Dreams album cover, to the E30 cabrio Ace gave Mitch when he came home from prison in Paid In Full, and the very 750il Tupac was killed in. It’s hardly a coincidence seeing the younger generation of black kids from LA (Tyler, Frank, Vince—the tasteful ones) not only sporting BMWs from that same era, but wearing them as a badge of honor, a rite of passage.

Once in that context, I believe the idea of the BMW as a status symbol is entirely thrown out the window. No longer does it represent actual luxury, but the perceived concept of luxury from an exact time and place. It functions as a reminder, it triggers that sensation of the dream. That “one day I’ll make it out of the hood” dream—whether an actual ghetto, or your own personal prison.

LA is a very vibrant and colorful city. How did you feel working here with a very stark black and white aesthetic? How does living in NYC affect you now?

Hassan Rahim: At 15, living in Santa Ana and being just detached enough from LA to not quite be a part of it (which clearly holds more teeming creative communities), it was through MySpace, SoulSeek, and other social media which I discovered my real interests, and many of my friends. Looking back I’m fortunate it happened this way—having no physical access to underground scenes or subcultures led me to dive deep into forums and file sharing networks. I became enamored with digging as deep as I could go, discovering things Santa Ana or even LA could never have offered.

Southern California was a strange place to grow up being there are no significant weather changes amongst seasons. That lack of emotional flux leads to a monotonous consistency in mood; it’s clear to see how this permanent vacation sunshine contributes to California’s much brighter aesthetic. By no means is that a bad quality for a city to have, but you could imagine the difficulty landing projects suitable for those possessing a much darker style (nonetheless paid projects).

While New York is historically much more receptive to starker aesthetics, unlike LA the city moves faster than you could ever keep up with. The pace has really challenged my work ethic and thought process in very positive ways, yet I don’t totally see New York as a home. I see it as a workplace; a long-term, but ultimately temporary, studio. I don’t think many others see it as a permanent dwelling either. You move here, spend about a decade building something; make sure you don’t burn out. Then you pack it up nicely and take it somewhere a little more quiet.

Still wondering why all the OG New Yorkers moved to LA?

Nothing beats stumbling on that perfectly esoteric blog, with cryptic images you’ve never seen in your life yet speak your language so vividly.

Tumblr has been a huge inspiration in the art and design community. What are thoughts on copying/recycling ideas and images? Where do you draw the line?

Hassan Rahim: Tumblr is extremely useful when used with care. Nothing beats stumbling on that perfectly esoteric blog, with cryptic images you’ve never seen in your life yet speak your language so vividly. On the other hand, that instant access to once rare information unfortunately also fueled a wave of copycat culture like nothing ever seen before. There are enough great essays about reblogging and attribution politics so I won’t bother. But as far as directly copying work is concerned, admittedly or not, every creative of this generation is surely guilty of being over-inspired at one point. If an image inspires you, that’s great—that’s fuel, a starting point to create something new. It’s ok to say “I like this texture” or “I’ll use a typeface like this”. But if you can’t take it somewhere new, you’ve missed the point of being inspired and are now part of the problem. Personally speaking, I now almost always avoid any singular image as resource. As I’ve matured I found myself way less interested in “snagging references” but instead seeking out specific books, magazines, and publications on a certain topic. You acquire a much deeper knowledge about any artist and their work. Learn their story, understand their process, study how their work has evolved through their career. What cultures and movements influenced them? Which movements were they a part of, and which ones did their work influence? I don’t quite know where the line is drawn, or even if a line can be drawn. But if you have to even ask yourself “is this too similar to the reference?” do yourself a favor: delete it and start over. If you aim to create something remotely worthy of delivering the same inspiration that image gave you, it has to be purely genuine and from the heart.

Since designers often speak a visual rather than verbal language, can you tell us through an image what you are looking forward to in the next year?

Hassan Rahim: