The Highest Form of Art: Designer Adrian Shaughnessy Talks Shop with Use All Five

You had a unique start to your design career, a method of learning that is rare today. Can you tell us about it and how you feel it compares to the experience recent graduates will face?

I didn’t go to design school. I trained in a studio in the pre-digital era. And yes, it’s hard to imagine it happening today. But if I were starting out now, I wouldn’t choose this route. Back then I thought I was being smart. How cool to learn on the job. Who needs design school when you can start working as a designer from the get go? But I now realize that I missed out on something that only a period of study gives you – the opportunity to experiment and make mistakes.

I had to learn everything at high speed, which meant that I couldn’t take risks, couldn’t indulge in experimentation, and couldn’t make mistakes. The result of this was that I became a conventional client-pleasing designer. It was only when I started my first studio (Intro, in 1989) that I developed the confidence to challenge orthodoxies and conventions, and take risks.

In a way, I’ve lived my life in reverse. Grads come out of school today jacked up on experimentation and a desire to set the world on fire. Over time, many of them (though not all) slip into a sort of default professionalism. I did it the other way round. I started as a conformist, and now I’m much more inclined towards experimentation and creative risk taking. I tell my students not to be me-too designers.

What are your thoughts on the current state of design education? How do you think it will change with the new resources of the digital age and how will this affect existing educational institutions?

Going back to the previous question, I should also point out that when I started out, in the 1970s, design education – in the UK at least – was very different from what exists now. The emphasis was on creating oven-ready, industry-compliant designers: so lots of time was spent designing wine labels, letterheads, and consumer goods packaging – pragmatic stuff – and not on thinking and broadening creative horizons.

But in the 1980s and 90s something happened that resulted in the radicalization of design education. Teachers became less concerned with turning out mini-professionals and industry-standard designers, and more concerned with turning out adaptable, versatile and agile-minded individuals. This revolution was mainly brought about by the lively design discourse that grew up in the 80s and 90s (mostly in the USA), where designers started to question the role of design – and the designer – in the culture. Not everyone took part in this discourse, but many who did went into teaching, and it’s those radicals who mainly lead design education today – something that I’m glad about.

My own view on design education – and its relevance in the digital realm – is that it is the role of educators to produce grads who are fit for an ever-changing discipline, and even more importantly, for an ever-changing world. Few of us will be doing the same work in 10 years time, and who knows what the design landscape will look like then. Education’s role is to equip designers for a future that is unknown. And of all the skills it needs to teach, critical thinking is the most important. Without this ability, we will only succeed in producing a generation of design automatons.

Can you tell us about your experience with podcasting with your series “Graphic Design on the Radio”? How do you view podcasting as an educational or inspirational tool? Are there currently, or will there in the future, be archives of your shows?

“Graphic Design on the Radio” wasn’t technically a podcast. It was a weekly show, broadcast live on ResonanceFM, the ad-free avant-garde radio station based in London. It was an extremely enjoyable thing to do. I invited designers to talk about their lives and their work, and asked them to play music that they liked or that had influenced them. Most designers I know are into music, but choosing six or seven records was often a surprisingly stressful task for them. I’d get emails at midnight the night before the broadcast asking if they could add this or that track to the list they had already sent me. But it was fun, and could only have happened on Resonance, and I only gave it up when it started to eat into my time, and I ended up finding it a chore rather than a delight. I love radio – and podcasts – but preparing for each show always involved more work than I bargained for.

I posted lots of the shows on my own website – but I took them down because I didn’t have a license for the music. My plan is to resume the show at some point, and also to repost the interviews.

One of the more thumbed volumes in our office is your 2005 work, “How to be a Graphic Designer, Without Losing Your Soul”. Has your business advice for designers changed since the economic collapse and transition of 2008? How have you seen the working world change since then?

I worry that this book is hopelessly out of date. I’m sure I’d have to update it every year to guarantee that it stayed relevant. Amazingly, though, it keeps selling, and has been translated into lots of foreign languages. But I have an odd relationship with the book. It was written when I had just emerged from 15 years of intense studio life. I had taken the decision to leave my studio to devote time to writing and consultancy work. And one of the projects I wanted to do was write a book about the stuff that designers never tell you about – how to handle rejection, how to deal with difficult clients, how do you talk about your work objectively, etc. But since I have now left that world, it is of less interest to me. So while I’m humbled by the people who tell me their copy is “well thumbed”, and I’m really pleased that it has helped many people, it represents a time of my life that has gone.

Why did you start Unit Editions? How did you want to influence the publishing or design worlds? How do you feel about using new tools like Kickstarter to support your projects?

This question follows on nicely from the previous one. Part of giving up studio life and no longer being a designer for hire, was to follow an instinct I had that designers could do more than just service their clients. Nothing wrong with that. It’s an important function on many levels – and I still do it on occasions. But I didn’t want to do that for the rest of my life. I wanted to be my own client.

So, after a chance conversation with Tony Brook, I discovered that we shared an ambition to be publishers. We’d both had bad experiences working for mainstream publishers, and we had the arrogance to think we could do it better. It was an ideal fit. Tony is a great book designer and art director, and all my ambitions are editorial. We also share similar tastes in art and design. So we started Unit Editions six years ago.

For me, Unit Editions is an example of how designers can own their creative production. Apart from the printing of our books, we are pretty much self-sufficient. As Unit Editions has grown we are now regularly approached by people who want to make books with us – designers, writers, and rights holders. We have some amazing stuff in the pipeline, and I think we’re gaining a reputation as a publisher with integrity.

Kickstarter looks as if it might be a viable route for us. Although nearly all of our books sell out, as an independent micro-publisher we are still under capitalised. Each book pays for the next. So although we are solvent, keeping the cash flowing is always a problem. Kickstarter is a way of easing the financial pressure. At the time of writing we have just had our fourth project 100% funded. I love Kickstarter and I’d like to think we could make good use of it.

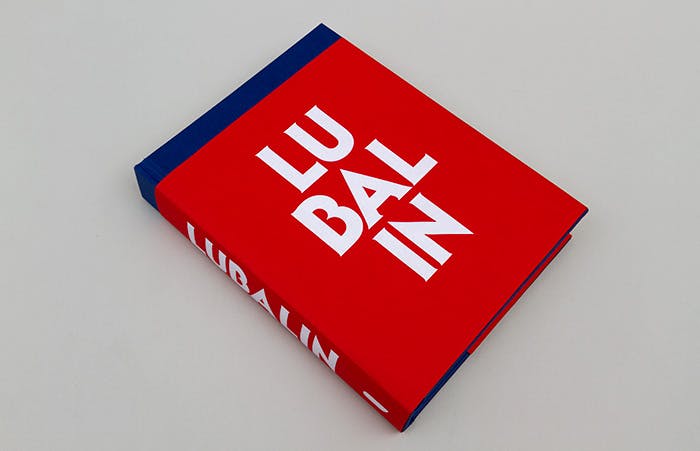

With the Unit Editions monograph of Herb Lubalin, you were able to shed light on a lifetime of typographic work that was mostly in an archive or flat files. How do you imagine legendary designers in the future being captured in a monograph, with the ubiquitous documentation of design work on the internet (like pinterest, dribbble, behance, etc). Will such monographs still be necessary?

This is an interesting problem. One of the few ways we can afford to do historical books – monographs on individual designers, or on schools of design – is if there is a physical archive in existence. If the work is spread all over the world, then the cost of photographing it – and studying it – becomes prohibitive. So physical archives are essential to our survival. We were able to do the Herb Lubalin book because of the wonderful Lubalin Study Center in Cooper Union, in New York. 90% of all Herb’s work is there, and is expertly looked after by Sasha Tochilovsky who we have worked with closely over the years.

The whole question around digital reproduction is still in flux. Digital work is made to be viewed on screen – so why move it to a printed format? And of course, once everything is digital, it will always be accessible (well, as long as the storage systems remain accessible). Will there still be books in 10 years time? Are Pinterest, Dribbble, Behance, etc., the archives of digital work? I actually believe that books will still be around for some time to come. They have already passed the eBook test – eBooks were going to make physical books redundant, but that hasn’t happened. And I firmly believe that art and design is best suited to the physical book format. Pinterest, blogs and most websites are template driven, and do not allow the dynamic layouts that can be done on the printed page. They are sterile by comparison.

We are working with Matt Pyke of Universal Everything on a monograph of his work. His output is nearly 100% digital – and most of it is either interactive, generative, or motion. So how do you make this work on the printed page? Well, watch this space.

What drew you personally to writing about design? Why is written/verbal communication of aesthetic ideas so important to designers and how can this skill be developed?

Mastery of the written word and mastery of spoken language are vital skills for designers to possess. No client ever accepted a design proposal without asking questions. And the more bold the proposal the more difficult the questions. Therefore, it’s vital that designers know how to talk about (in some cases write about) their work. I noticed that all the designers I admired were always able to talk and write about their work with clarity and objectivity.

This was one of the prompts for my own interest in writing. I knew that as a designer I had to get good at it. But I also had an interest in literature, and I’ve always been a reader. So when the design discourse of the 80s and 90s kicked off, I knew I wanted to be part of the discussion, and the only way I cold join that discussion was as a writer and lecturer. But writing didn’t come easily to me, and I’m still on a quest to become good at it. I admire good writing almost above everything else in life, and I think writing is the highest art form as it is the only art form that can effectively critique itself.