From left to right, Noam Saragosti, Erik Benjamins, Benjamin Critton and Heidi Korsavong in the living room of the Neutra VDL House.

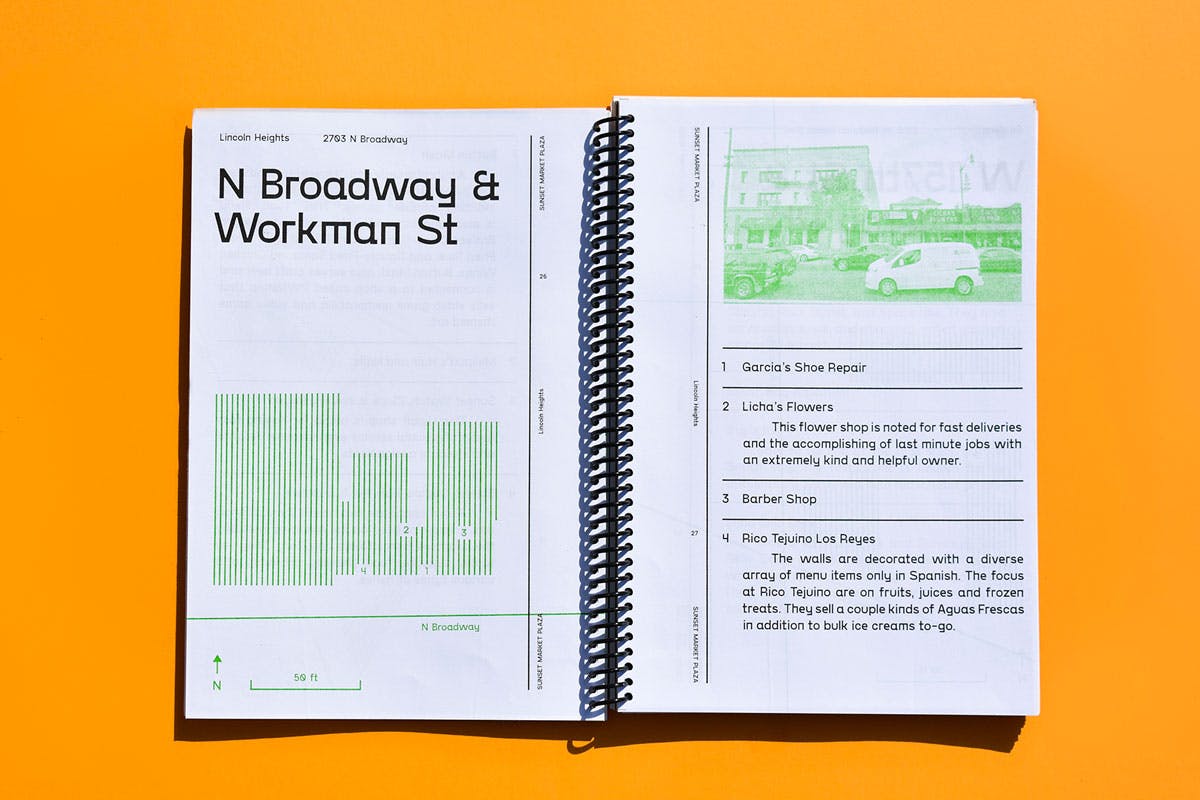

Overview

Neutra VDL welcomed visitors back into the iconic home for Built In, a group exhibition of site-specific works that speak to the historic architecture and larger story of the house and its inhabitants, co-curated by Erik Benjamins and Marta. Encompassing works by 32 Los Angeles based artists, designers, architects, and creative practitioners, Built In embraces the domestic setting of the show by inviting the artists to work with or even augment the various architectural structures of the celebrated modernist home. The curators’ intentionality in enlisting a fully LA-based slate shined a hyperlocal perspective on the space, enriching the dialogue between the work and the space. Visitors were encouraged to touch, smell and even sit on some of the artworks. The freedom to interact with these pieces in organic ways honored the domestic setting and the sensorial qualities of the works.

Visitors are encouraged to play with a ceramic puzzle built into the table.

Alex Reed, Puzzle No. 3 (for Neutra VDL House), 2021

Poplar, MDF, Ceramic, Lacquer; 47.0 × 42.0 × 13.0 in.

Photograph by Erik Benjamins

This exhibition was dear to us at Use All Five for a number of reasons. First, because Neutra is such a quintessential voice in what we’ve dubbed ‘the West Coast way’, but also because many of the artists in the exhibition had worked with our studio in the past and are people we admire and consider friends. “Use All Five” is a nod to the five senses, and our sensorial approach to design is something we consider unique. It’s this way of working that’s led us to organize various events and talks centered around the senses, –a series we titled Take 5– which showcased the work and ideas of various creative practitioners in Los Angeles.

For our first ever Take 5 event, we were fortunate enough to recruit Alex Reed (the ceramicist featured in Built In) to speak about the importance of touch in his work. At an ensuing Take 5 event where we showcased the work of Erik Benjamins, (Co-Curator of Built In), he and Emily Endo first met. Emily is an artist who works primarily in the medium of scent, and that day Emily was running a Take 5 workshop on crafting scents, who later asked to take part in the Built In exhibition. Emily’s pieces for Built In were scent-based artworks situated on each floor of the house, inspired by the various building materials used to construct the residence–aromas that evoked a sense of light and air, sharp metals and woods, which got progressively lighter and more transparent as one ascended the home.

One of Use All Five’s brand values is “Make Room at the Table”, and this is a living example of what we mean by that. We’re so proud and honored to be adjacent to so many exceptional people, and to provide avenues and environments where they can connect, trade ideas and eventually collaborate on things that we then get to genuinely enjoy as a studio.

History of The Home

The Built In exhibition began in the courtyard, where Erik Benjamins and Co-Curators Heidi Korsavong and Benjamin Critton spoke about the Neutra house’s past and its occupants. The history of the Neutra house and the history of the built-in architecture it contains play an important role in the dialogue the work creates with the home. The built-in is more than a simple shelf or countertop. The history of the built-in traces its roots back to the Arts & Crafts movement in architecture. This largely American tradition of architecture was a rebellion against mass production and a return to traditional craft methods and ‘romantic’ forms of decoration. While the Arts and Crafts movement hinted at some of the efficiency or “programmatic thinking” to-come in Modernism, the forms were decidedly less austere and more obviously shaped by the human hand. However, the Arts & Crafts movement went out of fashion in the early 1900s, coinciding with the rise in popularity of Modern Architecture in America. The Neutra House, built by Richard Neutra in 1932, exemplifies all the essential modernist elements through the use of a flat roof and emphasis of horizontal planes.

The Neutra Family

Equally important to the history of the home was the family who lived there. The Neutra family became quite the name in architecture and Richard had hoped to pass this legacy to their son, Frank, who was named after Frank Lloyd Wright. However, Frank was unable to fulfill the family’s expectations due to his severe autism, a diagnosis that sadly did not exist at that time. The nuclear family lived in the home until the last of them passed away. Richard and Dione Neutra’s ashes were spread in the courtyard and a plaque was placed in their honor. Frank Neutra’s ashes were also spread on the property and memorialized with a less prominent marker. In 1990 the Neutra VDL House was bequeathed by the Neutra family to Cal Poly Pomona University.

Featured Works

While the history and family dynamics may seem superfluous, it’s valuable to understand how the works address their environment. Upon learning about the memorial for Frank Neutra, Peter Tolkin and Sarah Lorenzen of TOLO Architecture decided to honor his memory more prominently through their work, which served as a memorial to the lesser-known son. This piece took the form of a bench engraved with Frank’s name that was cut to the exact shape of the wall, integrating the bench with the wall of the home and all its imperfections. This first built-in set the tone for the show, speaking to the home and the family that lived there.

TOLO Architecture, The Frank Lucian Neutra Memorial Bench, 2021

Plywood, Laminate; 55.0 × 19.0 × 19.0 in,

Photograph by Erik Benjamins

On the table nearby, an artwork by Emily Endo could be experienced. A glass vial of fragrance titled Nature Near (elm leaf, aluminum and white stone) inspired by the architecture and nature around the home. In the bathroom, an intervention by Office of BC could be easily missed. Tucked into the revolving toothbrush holder, a perforated sandstone emits a bespoke fragrance by the Institute of Art and Olfaction. White sage, laurel, and cedar recall the nearby Silver Lake Reservoir. The stone sourced from the nearby reservoir brought the outside in. Localizing the space by bringing nature and the larger community of Los Angeles together in the home.

An olfactory response to the VDL House is dispersed by way of built-in Hall Mack toothbrush housings in each of the main bathrooms. Each housing features a stone sculpture, which functions as an analog scent diffuser when activated by dropping small portions of the adjacent liquid fragrance, made in collaboration with the Los Angeles-based Institute for Art and Olfaction.

BC, VDL Scent Diffusers, 2021

Chrome-plated Hall-Mack fixture, Sandstone, Custom fragrance; 6.5 × 2.375 × 7.5 in (Housing) 4.0 × 3.0 × 2.25 in (Bottle on Rock)

Photograph by Erik Benjamins

Emily Endo, Nature Near, 2021

(Elm Leaf, Aluminum, and White Stone); Cast glass, ethyl alcohol, aroma molecules, violet leaves; 8.5 × 8.5 × 7.5 in (Vessel)

Photograph by Erik Benjamins

This theme continues in the flower arrangements throughout the home, thoughtfully arranged by Ikebana artist Kyoko Oshiro who continually refreshed arrangements throughout the house using found containers for the duration of the installation. This process again brings found objects, nature, and the outside community into the home. The ritual of maintaining the flowers made the home feel lived in. It was easy to imagine the Neutra family living in the space, arranging the flowers and tending to the home.

Kyoko Oshiro, Ikebana, 2021

Florals, Found Neutra House Vessels; Dimensions Variable

Photograph by Erik Benjamins

A pre-existing seating cushion in the main living room has had it’s stuffing replaced to include an electric heater, which warms the cushion to 98.6° F, or the temperature of the human body.

Brody Albert, Elijah, 2021

Foam, Electronic components; 26.0 × 26.0 × 5.0 in.

Photograph by Erik Benjamins

This presence of the family was felt throughout the exhibition, in some moments more subtly than others.

Summary

Built In brings the iconic Neutra home to life, conjuring conversation with the family who once lived there. The community that came together for the exhibition resurrected that energy simply by caring for the house and injecting new meaning into its existing structure – changing the flowers each week, watering the plants and paying homage to its former inhabitants. Benjamin Critton commented on this phenomenon in an interview with Wallpaper magazine:

‘This actually became one of the common threads: works that speak less to the house’s original author and architect, and instead commune quietly with Neutra’s family members.'

It’s interesting to note Benjamin’s usage of the term author to describe the architect of the home since the concept of authorship is critical in understanding our transition from the modern to postmodern style. Critical theorist Roland Barthes points out this cultural shift from the static or objective narrative to a flexible and subjective interpretation. In his essay “The Death of the Author”, Barthes proposes that meaning is no longer inherent within a text but rather spontaneously generated by the act of reading. While this change in sentiment marked the death of modernism and the grand narrative of its authors, it also embraced the birth of the reader in our transition to postmodernism.

Still from Koyaanisqatsi showing the collapse of the Pruitt–Igoe housing project, 1973

Randy’s Donuts in Los Angeles exemplifies the post-modern vernacular style, 2021

Throughout the exhibition two distinct world-views are on display, the narrative of the space and its interpretation by the works within. Built In embraces these two opposing points of view to create something greater than the sum of its parts. A synthesis of local and international style, an interplay between objective and subjective, iconic modern forms imbued with warmth.

The fountain by Charlap Hyman & Herrero features a seashell atop a stainless steel pole, contrasting the modern and vernacular styles.

Charlap Hyman & Herrero, Song of Saint James II, 2021

Shell, Polished stainless steel; 19.0 × 14.0 × 43.5 in.

Photograph by Erik Benjamins

A show as introspective as Built In makes us question the unique point in history where we find ourselves. What does an exhibition look like in the post-covid art world? With life shifting inward, how will art and the ways we view it be impacted? Does this shift in perception foreshadow the return of a built-in state of mind?

As culture tips back towards homesteading and we see millennials’ ever-increasing desire to conjure their dream home, the main concept of Built In seems to loom large over the design and interior-minded communities—through the notions of celebrating locality in sourcing of materials and in honoring architectural history. But it’s also about serving the human desire for something custom that fits perfectly in our environment—tailored to the activities and behaviors we idealize when we imagine how we and our spaces will come to interact.

With social media’s tendency to serve up images of idyllic and sublime interiors—often to the extent that our eyes begin to have difficulty parsing what’s real versus what’s 3D generated–millennials’ aesthetic expectations have gone through the roof. Factor in that debt is a real concern for millennials and that Covid has stressed the supply chain to the point of fracture, making ready-made furniture an inconvenience when its purpose is to be exactly the opposite, and suddenly it all makes sense.

Through it all, we’re spending so much more time in our homes, and there’s an ever-growing desire to connect with our environments in deeper ways, making the question for many: why not build it ourselves?

Built In has made us question popular narratives in the art world and culture at large. The exhibition proves to be as dynamic and complex as the city that serves as its backdrop–a place without which this exhibition could not be possible. It leaves us reflecting on the creativity of the artists and curators who so beautifully embraced the idiosyncrasies of this city and this home. Built In is so quintessential LA, and that is exactly what makes it so relevant.